Stock certificates

Almost two-thirds of the railroad certificates you will encounter in retail circumstances will be stock certificates. Many amateur sellers in online auctions fail to make accurate distinctions between stocks and bonds. Fortunately, there are several easy ways to identify stock certificates.

Horizontal format

Well over 99% of all North American railroad stock certificates were printed in horizontal formats. They are usually a bit wider and taller than ordinary office paper. Stock certificates printed before the 1880s were usually smaller and their shapes more variable. Certificates printed in California and Nevada tended to be much smaller even smaller. Most vertical format stock certificates are found among Mexican and Cuban certificates.

Look for the words "shares" and "stock"

Almost all stock certificates have wording similar to:

This is to certify that ____________ is entitled to;____________ shares in the Capital Stock of the XYZ Company."

There are normally lines in the body of text that were meant to be filled in with shareholder names and numbers of shares issued. Only a microscopic number of certificates are known from North America that were made out to the "bearer." Bearer certificates were those that companies considered the legal owner to be whoever held a certificate, regardless of how that person came to hold it.

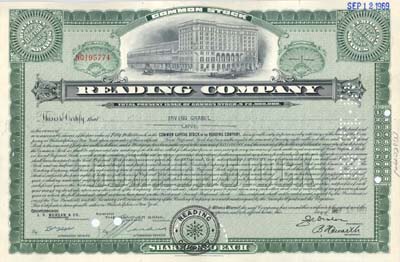

Par value

The majority of stock certificates display a "par value," either within the text or in the borders. Par value was the theoretical price that companies sold (or wanted to sell) each share for. A certificate with a $100 par value issued for 57 shares in the earliest days theoretically represented an investment of $5,700.

The meaning of "par value" gradually lost its meaning over time and is little more than an accounting term today. Collectors are advised to consult Investopedia and other financial sources for discussions of par value. These days, essentially all stock is considered "no par."

$100 par values appear on two-thirds (66%) of all recorded stock certificate varieties. Another 20% show par values of $50. The remainder show a large variety of par values in several currencies with the smallest being one-tenth of a cent. The largest stated par value recorded was $50,000 per share and can be found on shares of the Cuba Company.

Stock types

"Capital Stock" is the most common type. The two most common sub-classes of capital stock are common and preferred. Generally, only the most secure companies issued preferred stock. Consequently, common stock certificates are at least five times more plentiful than preferred stocks, although collectors usually pay the same for both types. Collectors will occasionally encounter convertible preferred stock certificates which allowed owners to convert preferred shares into common shares under certain conditions.

Vignettes

Approximately 95% of all stock certificates show a vignette (image) of some sort. Vignettes were primarily anti-counterfeiting measures, not just pretty pictures. While even the oldest stock certificates displayed some sort of images, vignettes became increasingly refined and complicated with time.

One does not need to be in the hobby long to notice that many varieties of certificates are highly similar, varying primarily in company name. In fact almost one-eighth of all varieties of railroad certificates share many of the same vignettes, border designs and underprints. These types of certificates are known as "generic" certificates and were produced in bulk by lithographic printing methods. Moreover, half of all generic certificates were produced by a single Chicago printer named Goes Lithographing Company. (That company is still in business and you can still buy its certificates from stationery stores and through the company's web form).

Small companies and startups were the main users of generic stock certificates because they could ill-afford to pay for custom-engraved certificates. Competition in the railroad business was always fierce, so companies that used generic certificates were generally under-funded and therefore failed to stay in business long.

Large, successful companies did not want their certificates to look like those from other companies, so usually avoided generic certificates.

While certain varieties of generic certificates are seen time and time again, the number of certificates issued by any specific company tend to be very small. As a result, generic certificates are much scarcer than their frequent appearances on railroad certificates might suggest. Even though generics represent over 12% of all identified "varieties," they account for only 2% of all stock certificates recorded so far.

Bearer certificates versus registered certificates

Only a tiny number of North American stock certificates were bearer stocks. The remainder were registered shares. That meant companies kept records of investors who owned stock.

Capitalization amounts

The capitalization value of a company is the total of the number of shares authorized times multiplied by par value. That represented the maximum capital that a company could raise if it sold every share of stock (as authorized by the state) at full par value. Capitalizations appeared on older certificates and gradually disappeared over time. In many cases, printed capitalization values were altered either higher or lower as the number of authorized shares or par value changed. Changes were commonly made by hand, rubber stamp, and overprinting.

Colors

Single-color black printing was the standard for many decades. Red ink appeared on certificates as early as 1837, although it was never popular. Brown borders put in an appearance in the mid-1840s followed by green in the 1850s. Green ultimately became the second most popular border color after black, probably because green was so closely associated with banknotes.

Many certificate colors are hard to accurately describe in person and impossible to describe from photographs. This project uses well-accepted color descriptions and avoid hair-splitting descriptions so common in the stamp hobby. There is no apparent relationship between colors and specific denominations. There seems to be a slight preference for using red borders on preferred certificates.

Denominations

Almost 75% of all stock certificates recorded in this project are described as "odd sh" certificates. That means they had no pre-printed values and clerks recorded the numbers of shares at the time of issuance.

Companies decided fairly early that pre-printed denominations would help them decrease labor costs. The earliest seen so far were 10-share and 20-share certificates printed for The Western Jamaica Connecting Railway in 1845. It seems very likely that 1-share certificates were probably used even earlier than that, although the earliest confirmed examples date from the 1850s. Stock certificates with pre-printed 2-sh, 5-sh, and 50-sh stock certificates also date from that decade.

100-share certificates are the second most popular denomination known (12.5%). They probably saw their first use during or slightly after the Civil War. The earliest recorded so far is from The Colorado & Southern Railway Co, dated 1869. It seems possible that "less than one hundred shares" (<100 sh) certificates appeared concurrently with 100-shares, but no dated examples have been found dated earlier than 1871. They represent 9.1% of the known population.

Punch panels

The oldest stock certificates displayed handwritten numbers of shares in both numerical and written form, much like checks and paper money. Engraving companies eventually added special panels along the bottom edges to allow clerks to indicate specific numbers of shares being issued by the use of a hole punch. The earliest punch panels usually indicated ranges of shares instead of specific numbers. The basic idea was to add a third confirmation of share issuance (along with numerical and verbal entries.).

Engravers eventually designed panels with two to five columns of numbers that allowed clerks to validate issuances as large as 99,999 shares. Punch panels were customarily engraved within or printed over right-hand borders. The earliest columnar punch panels appeared in the mid-1870s.

Serial numbers

Larger companies learned quickly that handwritten serial numbers hand caused many problems. Handwriting was costly and highly prone to mis-interpretation. Nonetheless, handwritten serial numbers were entirely legal and persisted until the last gasp of paper certificates.

All but a few legally-issued stock certificates show serial numbers. A few very early companies "re-used" or "recycled" serial numbers when certificates came were sold and transferred. Some recycled numbers are discernible by prefix or suffix letters. Recycling numbers never made a lot of sense, so the practice faded out fairly early in North America. Unfortunately, that early habit of recycling serial numbers causes great confusion in trying to decode the relationship between number and dates of issuance.

Serial number and share medallions

Most stock certificates display medallions, boxes, or lines for holding serial numbers and numbers of shares. While there is no set standard location, the vast majority of serial numbers appear in the upper left quadrant with shares at the upper right. A small number of companies reversed those positions and an even smaller number placed both numbers in the left third of certificates.

"Stock certificates" versus "share certificates"

American collectors tend to call them stock certificates while European collectors prefer the term share certificates.

Stubs

Printing companies usually delivered new stock certificates in 'stock books' of 100 or 200 certificates, bound on the left sides of certificates. As certificates were issued, clerks recorded names of stockholders, dates, and shares on both the certificates and the stubs. Certificates were usually cut out of the stock books with scissors which left distinct uneven edges that could be matched when certificates were transferred. While a seemingly crude method of verification, unevenly-cut stubs were useful in catching counterfeits. In much later times, certificate pages were perforated for easier removal.