What are gold bonds?

Almost 60% of all bonds in this catalog are classified as "gold" bonds. Gold bonds promised repayment in gold coin as opposed to silver coin or ordinary paper money. Why the difference?

Promotion

I suspect the idea of promising repayment in gold had more to do with promoting bond sales than anything else.

Companies promised two things when they borrowed money. They promised they would repay investors and they promised they would pay interest. Investors, on the other hand, were also concerned with inflation.

Inflation essentially means that the value of money decreases over time. Inflation works to the benefit of borrowers who get to pay with money that decreases in value over time. Conversely, inflation works against lenders for the same reason; lender receive money that is worth less and less as time does on. As a general rule, it appears lenders were willing to buy into the belief that gold was more likely to hold its value than dollars, pounds, or pesos.

While it took a while to embrace the concept, companies ultimately realized they could borrow money more easily if they decreased inflationary worries. One way to do that was to guarantee to repay loans in gold. Prevailing financial theory argued that gold was an effective hedge against inflation.

Appearance of the first gold bonds

Inflation had always existed, but it took the Civil War to really bring the problem front and center into the minds of ordinary investors. Between 1860 and 1866, inflation robbed the dollar of at least 70% of its value in the North, but even more in the South. Few companies had denominated their bonds in gold before the end of the Civil War. Then came a serious recession in 1872 that seriously crippled the country and halted practically all rail expansion.

To entice investment during threatening post-war times, many companies began promising repayments in gold coin. Based on surviving populations, only 6% of railroad bonds had been denominated in gold during the 1860s. During the next decade, the percentage more than tripled.

Gold bonds became increasingly fashionable from that time forward. During the 1880s, gold bonds probably constituted almost half of railroad bonds printed. (That assumes surviving bonds are somewhat representative of all bonds issued during that time.) Between 1890 and the early 1930s, gold bonds accounted for almost three-quarters of all railroad bonds!

What about the risk?

Promising to repay loans in gold was an effective sales ploy. Since the future was unforeseeable, It was also extremely risky.

Considering the percentage of bonds denominated in gold, it appears very few companies appreciated the risk of promising to repay investors in gold. In effect, they were wagering their companies on the beliefs that post-war inflation would remain under control. They were also betting that gold would always buy roughly the same quantity of goods and services over time, even in the face of inflation.

Every company executive knew the history of repetitive market panics. All knew more would follow. Probably none saw as far into the future as October 24, 1929. That day, now known as Black Thursday, represented the most devastating single-day sell-off of corporate shares in American history up to that time. The accepted rules of financial stability and recovery had changed radically. Economies around the globe had become highly interconnected after World War I. The crash of the market collapsed not only American business, but economies around the world. With few exceptions, countries fell into the Great Depression of the 1930s. With gold universally perceived as a haven of value, demand for gold, and therefore prices, crept upward.

While disagreements still swirl, there is no shortage of written commentary and opinions about the causes of both the crash and the depression. Nonetheless, by the end of 1932, global circumstances had driven world gold prices above the U.S. government's fixed Gold Standard price of $20.67 per ounce. Gold began flowing out of the U.S. economy in devastating amounts as the country repaid its foreign debts in gold. Gold prices climbed further in the early months of 1933. In April, newly inaugurated U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6102, "Forbidding the Hoarding of Gold Coin, Gold Bullion and Gold Certificates." It limited private ownership to $100 worth of gold and gold certificates and gave Americans until the end of May to trade gold coinage for paper. The order was not well-received by the American public.

Demand for gold on the world market rose further over the next two months. Getting a firm handle on exact prices is difficult and estimated mainly by comparing the dollar against other currencies, but gold had passed $25 per ounce in June. By that time, it had become increasingly obvious that It was clear that repaying corporate and public debt in gold was going to be impossible. The U.S. government was never going to sell businesses large amounts of gold while trying to pay its own foreign debts in gold. A literal torrent of gold was already going overseas. Even if sufficient gold coinage could have been found, paying inflated prices for gold in order to pay interest and principal would have bankrupted businesses anyway. Additionally, paying investors in gold would have been a violation of Executive Order. Yet, not paying in gold would have been a violation of bond contracts.

What were companies to do?

The end of gold bonds

While it could do little about the ongoing depression, Congress solved most businesses' gold-based problems with a resolution. In one fell swoop, Congress nullified every gold clause in every U.S. contract. That resolution (HJR 162) was subsequently formalized into law (73rd Congress, Chapter 48, 112-113) and said that requiring payment in gold was against public policy. It stated in clear language that, Every obligation heretofore or hereafter incurred, whether or not any such provision is contained therein or made with respect thereto, shall be discharged upon payment, dollar for dollar, in any coin or currency which at the time of payment is legal tender for public and private debts.

In short, debts were to be paid henceforth in lawful money, not gold. The period of high-flying gold bonds ended at 4:40 in the afternoon of June 5, 1933.

World gold prices rose further throughout the rest of the year and the U.S. desperately needed to get in front of the problem. Eventually Congress decided the century-old price of gold relative to the dollar was too low. It subsequently repriced gold at $35 per ounce under the Gold Reserve Act enacted January 30, 1934.

Although the jump to $35 could have been even higher, that price allowed the U.S. government to begin replenishing its gold reserves. The problem of the economy was far from being solved, but a crucial first step had been taken. Still, there remains another way of looking at the solution.

On the morning of January 30, 1934, the U.S. Mint had been able to buy an ounce of gold from miners for $20.67. By the next morning it needed to pay $35 for another ounce. Politely speaking, the act of needing to pay more legal tender for the same commodity meant implicitly that the value of the dollar had dropped. More crudely speaking, it meant that the U.S. Government had devalued the dollar by 59%. While gold miners were initially overjoyed that they would be paid more for their efforts, average American did not feel the effect immediately. As long as transactions were internal to the United States, the effects of the devaluation were subdued. After all, the country was in the middle of its second Great Depression. Hard times and seemingly high prices were the rule, not the exception. The devaluation was much more noticeable to companies and individuals doing business abroad.

It is also important to appreciate that most other countries had either devalued their currency relative to gold, or abandoned their gold standards entirely. .

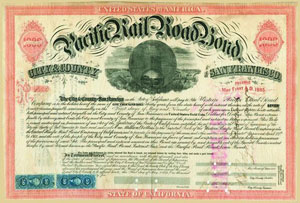

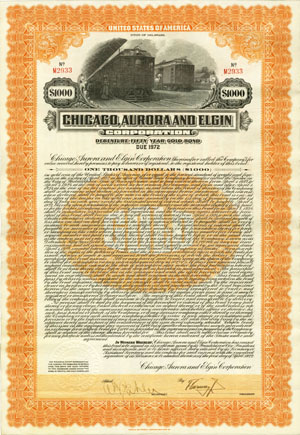

Identifying gold bonds

The word GOLD was usually displayed prominently on railroad bonds. Some bonds, especially earlier ones, displayed the word "GOLD" in bold underprints. The phrase "...in gold coin..." usually appeared in the text of bonds, right after a mention of the amount to be repaid. A few companies like the New York Central had foreseen possible repricing of gold and had stipulated the base value of gold by saying something like "...will pay to the bearer $1,000 in gold coin equal to the standard weight and fineness as it existed on the first day of October, 1913..." Some companies, and especially municipalities, recognized the long-term risk of denominating bonds in gold, and had purposely worded most of their issuances with phrases like "...will pay to the bearer $1,000 in lawful money on the first of January..."