A catalogers’ paradox

Several times a year, correspondents tell me how much they appreciate my catalog, but they think my prices are too high. Or too low.

I have never really discussed this issue in depth, but when it comes to prices, no one is supposed to agree with my estimates all the time.

A catalog needs to accomplish two tasks: it must tell what items are available to collect and the prices to expect in specific situations. My catalog predicts prices in the situation of well-attended live auctions in the U.S. Collectors must factor my estimates for other situations.

Estimating prices for collectibles means catalogers must live with a paradox. For estimates to be reasonably accurate, everyone must disagree.

Proof vignette of William Henry Vanderbilt from a steel plate engraving by Alfred Jones. Although no extant examples have been found, this vignette is known to have been used on dividend checks of the New York Central & Hudson River RR in 1879 and 1880.

Proof vignette of William Henry Vanderbilt from a steel plate engraving by Alfred Jones. Although no extant examples have been found, this vignette is known to have been used on dividend checks of the New York Central & Hudson River RR in 1879 and 1880.

Prices vary dramatically from auction to auction and dealer to dealer. An agreed-upon price estimate cannot possibly exist — not even for a single item. Instead of trying to find an agreed-upon price, the goal is to find a price that half of all knowledgeable observers think is too high and the other half think is too low. A few collectors and dealers will agree with a few prices, but ideally, the rest should disagree in roughly equal numbers.

The value at the point of equal disagreement is the perfect price estimate.

Think about the last time you negotiated a purchase. You desired something. The depth of your desire established your top-dollar price. Your goal was to acquire the item or service as far below your top-dollar price as possible.

The seller had mirror-image goals on his side of the deal.

He knew his minimum acceptable price, but wanted to win the highest possible amount.

If you successfully negotiated a transaction, you settled on a price somewhere in the middle.

Unless someone is in a financial bind, parties with the most information walk away from negotiations with the best deals. Negotiators should always realize that one party has better information than the other.

The primary purpose of a catalog is to give collectors information. How they use that information is up to them.

That is not to say that catalogers have all information. Far from it. Catalogers have only a fraction of the total information.

Still, catalogers have storehouses of both general and specific information. Information is what allows catalogers to accept constant disagreement without being personally offended.

For instance, a collector may tell me, “I strongly disagree with your $150 estimate for this particular certificate because I just bought one on eBay for $32!”

Believe me, I understand his point of view.

Back side of steel plate used to create the vignette of W.H. Vanderbilt shown above. You can see heavy hammer and punch marks clearly outline Vanderbilt’s profile. Adjustment to the plate in that area makes me suspect an earlier engraved background proved too dark when printed. Hammering on the back would have raised the surface on the front. By polishing the raised surface, Jones erased original lines and created a new flat surface for re-engraving. A machinist tells me that the hundreds of remaining hammer marks, even outside the engraved area, probably reflect efforts to keep the plate flat by relieving internal steel stresses.

Back side of steel plate used to create the vignette of W.H. Vanderbilt shown above. You can see heavy hammer and punch marks clearly outline Vanderbilt’s profile. Adjustment to the plate in that area makes me suspect an earlier engraved background proved too dark when printed. Hammering on the back would have raised the surface on the front. By polishing the raised surface, Jones erased original lines and created a new flat surface for re-engraving. A machinist tells me that the hundreds of remaining hammer marks, even outside the engraved area, probably reflect efforts to keep the plate flat by relieving internal steel stresses.

I also understand that my correspondent doesn’t realize how lucky he was. He doesn’t know that only three other examples sold on eBay in the past four years for $72, $90, and $127. Only 22 certificates are currently known out of a potential 40 examples. In the past fifteen years, only nine similar certificates have sold in live U.S. auctions with winning bids of $90 to $225 each. The record price was $325 in a 1997 German auction. One dealer currently lists a certificate on his web site for $275.

I look at complaints like this as merely under-informed. My fictitious correspondent did not have all the information that went into my $150 estimate. He had a single point of reference.

If someone is unimpressed by compiled historical information, then I suggest collectors ask themselves, “How much would a collector need to pay to find a second example in a reasonable amount of time?”

There is no definite answer. Obviously, a collector could buy one today for $275. If he is unwilling to pay more than $150, then he stands a good chance of winning one in a live auction in two to five years if he keeps his eyes open. Conceivably, a collector could get lucky and find another example on eBay, but I doubt that it will be very soon. I seriously doubt he will ever be able to buy another example for $32.

So, what is the true value for this certificate?

By accepting the pricing paradox, I hope that half of my readers will think my $150 estimate is too low, and half will think my estimate is too high. If almost everyone disagrees, then my $150 estimate is perfect.

300! New certificate varieties since November

|

November

letter |

This

letter |

| Number of certificates listed (counting all variants of issued, specimens, etc.) |

21,459 |

21,873 |

| Number of distinct certificates known |

16,265 |

16,565 |

| Number of certificates with celebrity autographs |

1,609 |

1,646 |

| Number of celebrity autographs known |

341 |

343 |

| Number of railroads and railroad-related companies known |

25,301 |

25,411 |

| Number of companies for which at least one certificate is known |

6,851 |

6,949 |

| Serial numbers records |

75,453 |

78,521 |

Why specialize?

Henry Clews. Steel plate engraving by A. I. E. Ritchie (?) from the frontispiece of Clew’s book, Twenty-Eight Years in Wall Street, 1888.

Henry Clews. Steel plate engraving by A. I. E. Ritchie (?) from the frontispiece of Clew’s book, Twenty-Eight Years in Wall Street, 1888.

Some collectors tell me they have neither a collecting specialty nor much money.

I hate to break the bad news, but the less money they have, the more they need to watch their spending. The more they need to watch spending, the more they need a specialty.

It will probably not surprise you to learn that most beginners tell me they don’t want a specialty because they intend to own one of every variety ever printed.

Owning an example of every variety would be wonderful. There’s just one teensy, weensy problem...

It is impossible!

Collectors are doubtlessly misled by the erroneous idea that prices reflect rarity. They naturally assume that sub-$1,000 items cannot possibly be rare.

I apologize for failing to communicate this fact more clearly, but there are hundreds of genuinely rare certificates that have sold for less than $50. In the coin hobby, equally rare items might sell for tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars!

Collectors prove day after day that they do not appreciate the super-rarities of our hobby. Speaking strictly about railroad certificates, I can testify that hundreds of varieties are represented by only one or two examples. A thousand varieties, maybe two thousand, are represented by fewer than ten examples! Owning one of those rarities is an achievement and honor. Trying to own them all is a recipe for failure.

I am not against dreaming, but how can collectors enjoy a hobby when the first thing they do is set themselves up for failure?

A satisfying and achievable result might be to own some of the earliest certificates ever printed in the United States. Another satisfying result might be owning a few of the rarest certificates from a particular state, region, or company. Some collectors find it satisfying to own the signatures of all major railroad executives. I know one person who collects certificates with autographs of historic stock operators. I know many collectors who find enjoyment trying to collect certificates from companies located in their home states.

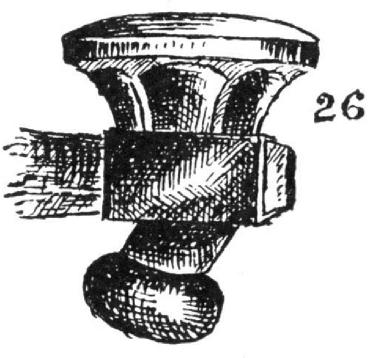

Engraver’s hammer. From illustration in A.M. Hind, A History of Engraving and Etching, 1923.

Engraver’s hammer. From illustration in A.M. Hind, A History of Engraving and Etching, 1923.

Regardless of the specialty, the more clearly collectors identify the results they want, the greater their likelihood of gaining satisfaction. When they precisely identify the results they desire, they discover their specialties.

When collectors make this crucial discovery, their collecting goals become crystal clear. For instance, maybe they want their collection to represent one certificate of every ancestral company of today’s Union Pacific. Then why do they have a Boston and Providence certificate in their collection? If they want to own an example of every certificate ever issued in the state of Kansas, then why did they buy a Blue Ridge bond from South Carolina?

Specialization is about money. If a collector is a billionaire, the need for specialization is unimportant. However, according to the book, The Millionaire Next Door, even millionaires need to watch their checkbooks once in a while. The more limited collectors’ resources, the more they need to watch their purchases.

There are a couple ways to uncover the results you want.

I bet you probably already have the framework of a specialty started. Narrow it down by going through your collection and looking hard at every certificate. Imagine separating everything into three or four piles. What piles would you make? States? Companies? Streetcars? Engravers? Vignettes? Transitional certificates? Bonds? Dates? Autographs? Dates?

If you can force yourself to group everything into a few number of piles, you will discover your specialties.

Another trick is the “justification strategy.” Imagine talking with a non-judgmental collector and justifying why you bought every certificate. As diverse as your collection may be, I bet the act of justification will tie most of your collection together into specialties.

As you self-discover more about your true collecting interests, the more likely you will notice that some of your purchases were ill-planned. Maybe you should get rid of those certificates. Not this year. Not next year. But sometime after prices improve.

Once you discover your specialty (or specialties), you will be able to look at your future purchases more clearly. You will be able to ask, “If I buy this new certificate, will it

help take me get closer to my goal of ______________?”

Discovering a specialty will be liberating ...and it will save you money.

Gravers used in etching and engraving. Cross-sections 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, 2a, 2b, 2c, and 2d show the shapes of various gravers. From A.M. Hind, A History of Engraving and Etching, 1923.

Gravers used in etching and engraving. Cross-sections 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, 2a, 2b, 2c, and 2d show the shapes of various gravers. From A.M. Hind, A History of Engraving and Etching, 1923.